Ad Astra Blog

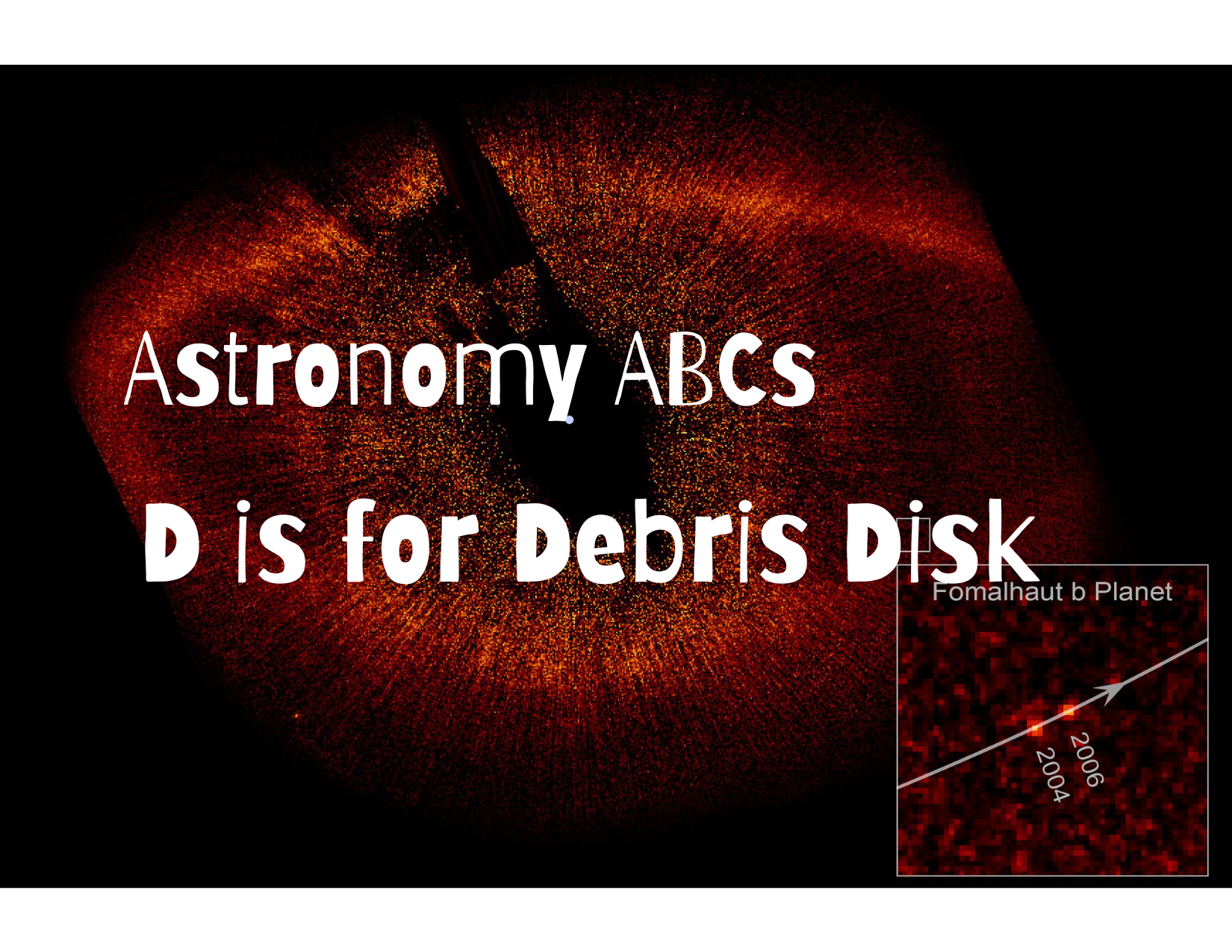

Astronomy ABCs: D is for Debris Disk

Happy Honda Days, everyone! It’s December, which start with D, which is also the next letter in Astronomy ABCs! And this month D is for debris disk!

Happy Honda Days, everyone! It’s December, which start with D, which is also the next letter in Astronomy ABCs! And this month D is for debris disk!

A debris disk in astronomy is pretty much what it sounds like: a disk made up of debris from some formation process that orbits a celestial body. Usually astronomers talk about debris disks when discussing the formation of planets around a star, so a debris disk in this case would be the gas and dust left over from the formation of a star that orbits that star in a disk.

A debris disk shouldn’t be confused with a protoplanetary disk. Protoplanetary disks have much more gas, but in debris disks this dust is nearly gone. Protoplanetary disks also tend to be found around younger stars than debris disks, leading to the hypothesis that protoplanetary disks evolve into debris disks over time. The link between protoplanetary disks and debris disks is an active area of research.

The term “debris disk” sounds like what is left after something catastrophic happens. And really, I guess that’s true! But not catastrophically bad. It’s the natural consequence of the formation of stars.

Stars form out of clouds of hydrogen gas and dust called nebulae. A star-forming nebula like the Orion Nebula will form many, many stars. In the very earliest stage of a star’s life, it is still surrounded by an envelope of gas and dust. This material will form planetesimals (basically a general term for small bodies like asteroids and comets), which will continue to collect material until they form planets. This might go on for a few tens of millions of years, but the pressure from the radiation given off by the star will eventually clear out all the teeny tiny bits. But this is just the beginning of the debris disk. Collisions between these planetesimals may cause a second generation of dust in the system.

OK, so we have these planetesimals flying around, potentially crashing into each other and creating dust that turns into a debris disk. Dust grains in a debris disk tend to be about 10 microns wide at their biggest. For reference, a human hair is something like 50 microns wide, so these dust grains are pretty tiny. These tiny grains will further collide to make even smaller, sub-micron sized pieces that won’t stick around the system for long. These dust grains could also spiral into their host star. These processes mean that, without any process to replenish it, the debris disk will only last about 10 million years. However, the cycle of collisions often keeps the debris disk around for longer.

Studying debris disks around other stars can shed light on the formation of our own solar system, but it’s also especially relevant for astronomers who want to find exoplanets, or planets around stars that are not our Sun. You see, for collisions to happen, planetesimals need to have their orbit altered in some way. Gravitational perturbations can draw two objects together and bam! Collision. The central star could cause this, as could a second star in a binary star system. But you know what else could cause these perturbations? Planets. So how can astronomers narrow down where to look for planets? Find systems with a debris disk. These systems are easier to spot and, while it doesn’t guarantee a planet exists there, it increases the odds.

Even though debris disks are easier to find than individual exoplanets, they are still difficult to find. Because of the thermal emission properties of dust grains, usually debris disks are detected with telescopes designed to detect relatively cool things out in space. It’s hard to believe that we can actually use telescopes on Earth to see other stars in enough detail to make out their disks and, possibly, detect planets. I’m never not astounded by what we’re able to learn!

Featured image credit: NASA, ESA, P. Kalas, J. Graham, E. Chiang, E. Kite (University of California, Berkeley), M. Clampin (NASA Goddard Space Flight Center), M. Fitzgerald

Astronomy ABCs: B is for Blackbody Radiation

Ah, hello. It is a new month and here I am, trying to fulfill the promise I made to myself to write about astronomy every month. Rather than try to come up with something very clever to write about, I decided to use the English alphabet to guide my way. Last month - the first month of this journey - was A, which of course stands for Astronomy. As is customary, B follows A, so this month let’s dig into blackbody radiation.

Ah, hello. It is a new month and here I am, trying to fulfill the promise I made to myself to write about astronomy every month. Rather than try to come up with something very clever to write about, I decided to use the English alphabet to guide my way. Last month - the first month of this journey - was A, which of course stands for Astronomy. As is customary, B follows A, so this month let’s dig into blackbody radiation.

So…what’s a blackbody? A blackbody is an object that absorbs all light that hits it and emits thermal radiation. Atoms in the blackbody will start to heat up and vibrate faster and faster. As it heats up it will emit electromagnetic radiation - aka light - until the absorption and emission are in balance, i.e. it is in thermal equilibrium with its surroundings.

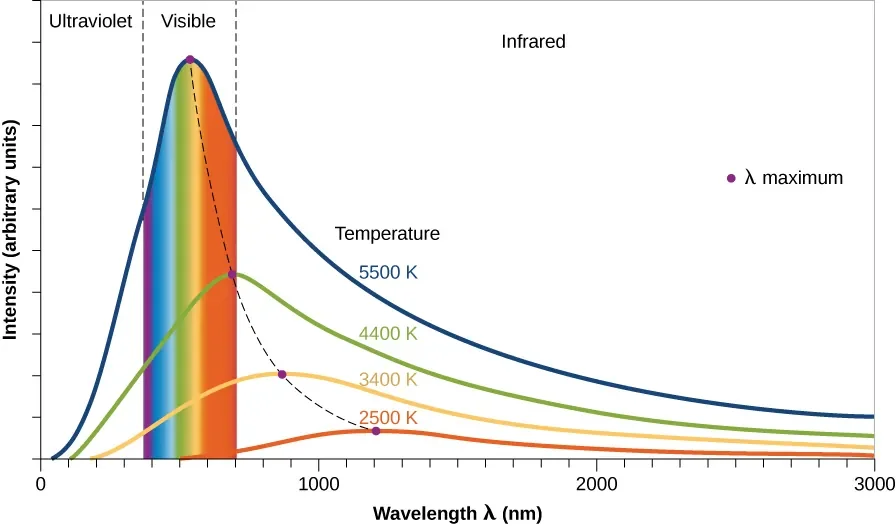

The radiation from a blackbody has three characteristics that make it useful in astronomy. Check out the plot I shamelessly stole from the OpenStax Astronomy textbook.

Blackbody radiation illustrated for several temperatures.

This plot shows the blackbody radiation curve for different temperature objects. The vertical axis is intensity - basically how many photons our objects are emitting - and the horizontal axis is wavelength.

There are a few things to notice about the blackbody radiation curve:

First, the spectrum is continuous. These blackbodies are emitting photons at all wavelengths at once (but not all equally, which is important). These blackbodies are just bundles of atoms and molecules. These atoms and molecules will vibrate and bump together at varying speeds. Some will slower than average, some will be faster than average, but most will emit energy at some average value (the peak in the plot). But it’s the spread of these energies that gives us the blackbody spectrum we see.

Second, hotter blackbodies emit more radiation at all wavelengths compared to cooler blackbodies. This is because hotter atoms and molecules vibrate and collide more often, which causes them to give off more energy.

Third, check out the peaks of each temperature blackbody. Other than the height of the curve, what jumps out at you? To me what jumps out is the shift of the peak redward as the temperature of the blackbody goes down. In other words, the peak of the blackbody moves to higher (redder) wavelengths as the temperature decreases.

How does all of this help us with astronomy? Well, it turns out that stars emit radiation like a blackbody! This means that we can use what we know about the blackbody curve to make a thermometer for stars.

There’s a nice mathematical relationship between the wavelength that has the highest intensity in a blackbody and the temperature. It’s one of those important equations that gets a name: Wien’s Law:

This says that the wavelength of maximum intensity (in nanometers) is equal to a constant divided by the temperature (in Kelvin). What this allows us to find the temperature of a star by just measuring its spectrum!

This also means that the color of a star can stand in as a rough approximation of its temperature. Light gets more energetic as its wavelength decreases, and each wavelength corresponds to a particular color. Stars with a max intensity at low wavelength will have hot temperatures, and stars with a max intensity at large wavelength will have lower temperatures. The smaller the wavelength, the bluer the light, and the longer the wavelength, the redder the light. So if we wanted to compare the temperature of a star that appears red to the temperature of a star that appears blue, we could say that the blue star is hotter than the red star just from color alone! Pretty cool!

I got this post in just under the wire for October, but I did do it. I don’t need your praise, I’ve clapped for myself. I hope you stop by next month for more ABCs of Astronomy.

Astronomy ABCs: A is for Astronomy

I used to write the way I breathe. It was effortless. I would have a thought and I would write it down, which changed very little in the distance between my head and my fingers. I haven’t written much in a while, though I’ve tried to create systems that encourage it. I really did want to learn and write a bunch about Venus, but…well. You can see how that turned out.

I used to write the way I breathe. It was effortless. I would have a thought and I would write it down, which changed very little in the distance between my head and my fingers. I haven’t written much in a while, though I’ve tried to create systems that encourage it. I really did want to learn and write a bunch about Venus, but…well. You can see how that turned out.

Part of my job is writing a monthly public science talk. Every month I choose a topic and write a roughly hour-long presentation on it. I script out every talk. I know that this isn’t necessarily “good” practice among scientists, but I do it for a couple of reasons:

I get really nervous when I’m speaking. A script is like a security blanket. If/when I get so nervous that I forget the point of the slide, I have something to fall back on.

The script is a little gift to future me. Once a talk is written, I’ll give it whenever. It’s on the schedule for a certain month but if a group wants to hear it 4 months later, who am I to say no? I write a script because I know I am forgetful. A script allows me to pick up the talk months later and know exactly what I meant to say.

It just helps me weave a story. The flow from slide to slide is better.

I’ve been in this position for a little over 2.5 years and I’ve written 36 individual talks, most of them hour-long public lectures. I was curious to see how much writing a year of public lectures was, so I counted up every word of each of the 12 scripts I wrote in 2024. The result: 65,491 words. A 200 page book - depending on page size and formatting - is 50,000 to 60,000 words.

Ah! No wonder I haven’t been writing more on my own! I wrote a book last year. And, since my 2025 lectures are roughly the same length as my 2024 lectures, I’m sure I’m well on my way to writing a book this year, too.

I really thought I had lost any skill I had as a writer because I couldn’t turn it on at a moment’s notice. But seeing the amount I wrote last year compiled in one place made me think that maybe I’m just trying to force myself to write about things that don’t fit into my life right now. If I may say so, the lectures I wrote are good. I think I explain complex things pretty well to a lay audience.

All of this was a long preamble before introducing a new series: Astronomy ABCs. Every month gets a letter and I will write at least one piece on an astronomical concept that begins with that letter. Why should you trust me when I have failed so many times before? I don’t know, maybe you shouldn’t. But I did spend an hour yesterday making a list of topics organized alphabetically. Do with that what you will.

The best place to start in the alphabet is the beginning, and for English that letter is A. A is for Astronomy.

And listen, I thought about this. A could have been for Accretion Disks. Or AGN. Or Asteroid. Or Airy Disk. But if I’m going to start a series of astronomy-themed posts, I thought it might be a good idea to talk about what astronomy is.

Astronomy (or astrophysics, if you prefer) is the scientific study of space and the objects and phenomena we see there. It brings together physics, math, chemistry, geology, and computer science to figure out how galaxies, planets, and the Universe itself works. There are many subfields in astronomy - cosmology, extragalactic astronomy, planetary science, exoplanet astronomy, stellar astronomy, the list goes on - but if it studies something in space, I consider it under the umbrella of astronomy.

Astronomy is also incredibly old. Early civilizations used observations of the sky to keep track of days, months, and seasons, many developing a complex mythology that encodes generational astronomical knowledge.

With a few exceptions, astronomy is an observational science. At least right now, we can’t travel to a nebula and gather a sample of cosmic dust and gas to study. We need to view our subjects from afar using telescopes that are sensitive to different wavelengths of light. The closest we can get to bringing a bucket of star back to Earth is using telescopes to gather light from far off objects as it travels in our direction.

Over the next several months I plan to write explainers on astronomical topics ranging from the small to the very, very large, from close by to very far away, from massless to massive. Some topics I’ve identified are topics I know well. Others…less so. If I do this right then we all learn something.

Next month is the letter B. What will I write about? Black holes? Blue stragglers? The Big Bang? Something else? Check back to see!